Dear Princess ‘Ishka,

Can you will to believe that p and therefore believe that p, where p is a proposition like “Donald is the greatest expert on climate issues”? This is a question M, M and I asked ourselves. I am a little embarrassed, because I am not sure about what conclusion we reached specifically, but it definitely was an intense conversation.

In conventional philosophy of mind, beliefs are world-guided mental states, which tend to adapt to the world or to how we perceive it. They are commonly distinguished from desires because desires are, to a certain extent, independent of the world around us (I can desire to grow wings and fly to the moon and back undamaged). Beliefs differ also from intentions, which are mind-guided mental states oriented at performing changes in the world (I intend to paint all yellow cars purple, just for fun).

If beliefs are world-guided, how is it possible that you can intend or desire to believe something and thence believe what you intended or desired? This question might sound complicated, but it is about something that people often say, especially about their political opposers. You might have already encountered propositions of this kind: “Donald’s supporters believe what Donald says even if it is not true, because they want to.”

I want to argue that to believe in virtue of one’s desire or intention to believe is, at least in noncontroversial cases, impossible. First thing to notice is that you usually form beliefs independently of your will. You might ask yourself “What color is the next car I will come across?” and then you might try to compel yourself to believe that it is yellow. But then you see it approaching and light produces on your retina a reaction that makes you see it purple. That’s it, you believe it’s purple and you can’t do anything about it, no matter how hard you try.

However, cosmological, moral or political beliefs might be different in this sense from perceptual ones. It might be easier, with more complex data, to “fake it till you make it” or to condition yourself into thinking something you would otherwise not think. Or so it could be argued.

Think for instance about someone whose family has been hard core leftist for generations. This person might come to believe something just because he is accustomed to do so, or even just because he wants to continue the family’s tradition. I think that this argument is wrong if it leads to the possibility of genuine self-conditioning. Just as in the case of the approaching car, a new political idea might strike him and produce changes in his beliefs independently of his will. All he can will to do is to stay away from different ideas, or block excessively critical reflective assessment of the opinions he already holds.

However, to keep a distance from different ideas and avoiding reflection are not ways to condition yourself. They are rather ways in which you allow only a certain environment to condition your beliefs.

At this point, two objections can be raised: 1) the environment around us is often a social environment, that can be modified with collective intentionality; 2) there are certain psychological cases in which self-conditioning is not only possible, but even encouraged by psychologists.

With respect to 1), I agree. The social environment is conditioned by collective intentionality, even if it is difficult to argue that a collectivity can have reflective control on what it desires and intends. So, to a certain extent, beliefs remain independent from the possibility of self-conditioning. From this perspective, the social environment is mind-guiding in the same sense as any other environment guides the mind. The possibility of believing is out of the reach of our self-conditioning, and possibly even more out of control than in cases of non-social environments.

In the case of 2), which was specially pushed by M, I would argue that what the psychological patient is encourage to do is not to produce beliefs about herself with her willpower, but rather to construct narratives that produce mind-guided attitudes (intentions and desires) that make those narratives self-fulfilling.

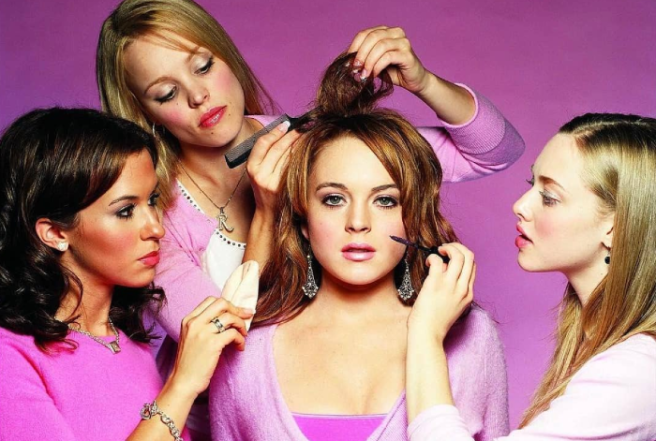

Consider the case of a bullied girl, who wants to be cool, join the cheerleaders and forget about her self-worth to become the house pet of some brainless straight guy. She tells herself the story, in which she is not a loner, a loser and a freak. Then she goes to school and is bullied, ridiculed, isolated and left even more depressed than before. Unless she gets mad, in a state of total delusion where the very concept of belief doesn’t make sense anymore, she must deal with the situation she is in. Her beliefs clash with her narrative, but does this mean that she should give up her made up narrative?

Not at all! Indeed, she might be so determined that, little by little, with her practical intelligence and her willpower, she can “fake it till she makes it”. Afterwards, her beliefs will reflect the new situation and realign with her narrative. Otherwise, she might be better counseled, bite the bullet, ignore the bullies, and become a realized human being with talent and self-worth.

Beliefs can be wrong in all sorts of ways, but willing to believe and therefore believe is impossible. This also means that our minds can be conditioned much more from the outside than from the inside. Thus, we need to constantly be open to debate with people with different ideas, and allow the greatest variety of environments to affect us. Otherwise, we seriously might start believing that yellow cars are not produced because of complicated conspiracies, while in fact it was my intention to paint them purple.

Forever yours,

‘Miasha